Vita

The life of Hanns Heinen

Johann Jakob Josef Heinen, known as Hanns, was born on 5 October 1895 in Bauchem, a small village in the district of Geilenkirchen to the north-east of Aachen. His father, Johann Heinen (1845-1923), came from the small village of Randerath and was an official in the Prussian judicial service. He was 50 years old at the time of Hanns’ birth. Hanns’ mother, Maria Anna Catharina Hubertina Dresia (1862-1936), was of Italian descent and came from the hamlet of Dürboslar near Jülich. She was 33 years old at the time of his birth. Both of his parents were Catholic from families of farmers and craftsmen in the Lower Rhine region of Germany.

He was the third child and youngest son of the family. His two older siblings were his highly talented brother Theo (Theodor) and his sister Fine (Josefa).

In the second year of little Hanns Heinen's life, the family moved to Solingen in the Bergisches Land. It was here that we went to the local primary school and the Gymnasium on Schwertstrasse, from which he graduated on 4 August 1914 with the “Zeugnis der Reife”. At the time, Roman and Greek classics played an important role in the Gymnasium. His talent for poetry was noticed by one of his teachers, the white-bearded Professor Thamheim, who would continue to impress and influence the young Heinen.

He writes about his childhood “...my childhood days were, albeit banished to the narrow sphere of insufficient wealth, outshone by the harmonious serenity of the Catholic faith...” He wrote his first poems at the age of fourteen. At that time, he was thinking of either becoming a Catholic priest or a teacher of German and ancient languages, as he was very fond of these subjects. However, the outbreak of the First World war put an abrupt end to these deliberations.

The young Heinen was sent off to war in April 1915, where he remained in action on the Western Front until 1918. He counted his time as a soldier on the frontlines at the Battle of Verdun as some of his worst experiences of the war. His brother Theo, with whom he had a very close relationship, was killed on the front. Heinen would later name his eldest son after him. With some interruption due to the war, Hanns Heinen studied philology, economics and law in Münster, Bonn and Strasbourg, where he became an ardent socialist. He wanted to help bring about change, so he decided to pursue a career in journalism.

The year 1919 was one of the most important years of his life in a number of ways. On 28 November of that year, he married the love of his life, Erna Heinen–Steinhoff (1898-1969), whose family resided at the Haus Ahse manor near Soest. Her family was Protestant, and mixed marriages were uncommon at the time. Their marriage would produce four children. In the early 1920s, his two sons Hans-Theo and Gunther were born in 1921 and 1923 respectively. The mid-1930s saw the birth of his two daughters Gabriele Eleonore (1934) and Bettina Sabine Cornelia (1937). Erna Heinen–Steinhoff refused the “Mother’s Cross of Honour” that was presented to her after the birth of her last child.

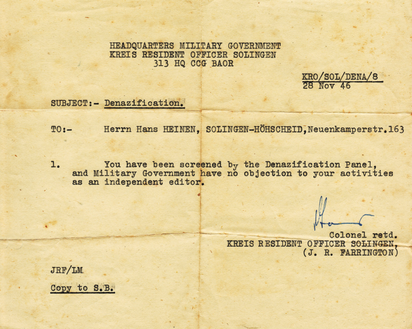

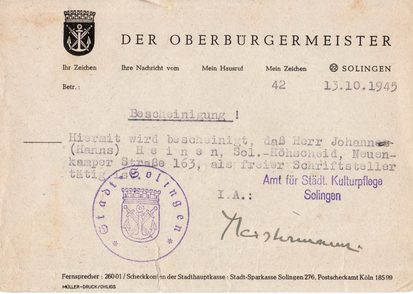

In 1919, his first work was published by the Xenia publishing house in Leipzig. It was a historical stage play entitled “Spartakus”, which at the time of the revolutionary “Spartacist uprisings” was a very provocative title. A second edition of his play was subsequently published by the Solinger Tageblatt the same year. It was also in 1919 that he began his journalistic career. He became the editor of the Solinger Tageblatt before working his way up to become editor in chief of various newspapers. He then worked as an independent journalist for the latter part of his career, up until his untimely death on 23 December 1961.

Extract from the official address book of 1932: Between 1928 and 1932, Hanns Heinen, whose real name was Johann Heinen, lived at the small Bertramsmühle estate (No. 02) near the Wupper river close to Solingen. The family moved to the “Black House” in Solingen in December 1932.

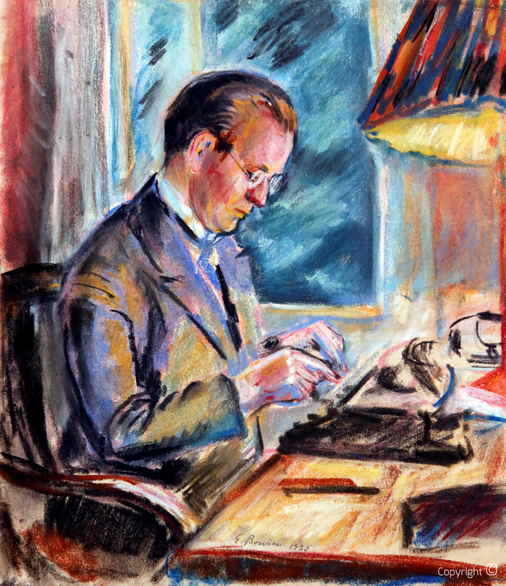

At the end of the Second World War, Hanns Heinen fled from Solingen to the small village of Kreuztal – Eisenbach near Isny in the Allgäu region. He ventured over 50 hours by train to get there. His family had already been evacuated there, and there he also met his friend the painter Erwin Bowien (1899-1972), who had been living underground. A warrant for his arrest arrived by telegram in Kreuztal. However, the local post mistress did not hand it over to the authorities but rather burned it right in front of him.

Hanns Heinen was installed as Mayor of Kreuzthal - Eisenbach after the allied occupation of the village began.

However, later on in 1945, Hanns Heinen left the Allgäu and returned to Solingen, where he found his house overcrowded with refugees.

This was the beginning of a very difficult period of intense poverty and hunger. During this time, Hanns Heinen spent a lot of time writing and composing poems, including his magnum opus: “The Road of the 30 Years”. He became involved in politics and attended the founding conference of the Rhineland and Westphalian Writers’ Association at Ingenhoven Castle in Lobberich in June 1946 (now a district of Nettetal). From 1948, he worked as editor in chief of the “Eberswalder Offertenblatt”, which was a renowned business newspaper at the time.

Invitation to a reading of Hanns Heinen’s poems at the Volkshochschule (adult education centre) in Solingen on 20 January 1949. As was often the case, the poems were recited by his wife.

It was in the years that followed the war that he helped his wife set up the artists’ colony at his house - the so-called Black House in Solingen. The artist Erwin Bowien would move in to the house upon returning from exile in 1945. His daughter Bettina Heinen – Ayech would later be influenced by Bowien and become an artist herself. The Hamburg-born artist Amud Uwe Millies would also move into the house in 1955. During this time, many cultural and literary salons were held in the so-called “Black House”, to which Hanns Heinen regularly invited an array of guests.

Aside from economic works (including the Road of the 30 Years, the Fever Curves of Solingen’s Industry), he left behind volumes of poems (the New Stream, the Book of Guilt, From the Middle of Life) and plays (The Royal Game, Messiah, Spartakus and Ekkehart). He is buried at the forest cemetery in Solingen-Ohligs.